You (may not) Know JS

A wild Closure appeared and it's super effective

Hello my fellow JavaScript developers 👋

Back in my first job I quickly realized that the FreeCodeCamp front end course I had finished wasn't nearly enough to deal with the hardships of creating scalable and maintainable D3 chart templates. A fact that was confirmed when my boss suggested I read more about the insides of the language, heavily implying that I'd be fired if I didn't 🚀

My senior developer at the time suggested the well known You Don't Know JS books, a well written series of books about the intricacies of the language. And by the end of the first book I had realized that I did not have the foundations of the language, and acquiring them made me more productive by cutting down on the time spent googling around how stuff was supposed to work.

So the goal of this post is not so much to imply that you don't know how to declare variables as to declare that you, my friend, may not always be aware of what's going on under the hood and teach you some use cases for those mechanisms.

And without further delay, let's list some quick facts and concepts you probably did not know about JS

Type coercion

Type coercion is the process of converting value from one type to another. Since JavaScript is a weakly-typed language, it converts two different typed variables when you use its operators.

A great cheat sheet for the type coercion principles can be found here 👈 If you're still wondering, the best practice is to not learn that whole table and stick with using strict comparison. REALLY.

Let's get to some quick facts straight about operations.

Difference between == and ===

There a difference between using == and === when comparing two variables. The first only compares value, it's called abstract equality, while the latter compares type and value and is called strict comparison. This is why 1 == "1" //true and 1 === "1" //false . In the first comparison we have implicit coercion

Difference between null and undefined

When strictly comparing null and undefined, JavaScript returns false , this is because undefined is the default value for undeclared values, function that doesn't return anything or an object property which doesn't exist. While null is a value that has to be explicitly given to a variable or returned by a function.

In the end if you also check, the type of both variables is different. typeof null //"object" and typeof undefined //"undefined".

Short Circuiting Logical Operators

Because who needs ternaries

Now here's another example of where JavaScript's type coercion comes into play. For rendering React components, you come across the following patter quite often: const render = () => loading && <Component/> . Usually loading is already a Boolean type variable, but sometimes we can find something like const render = () => data.length && <Component data={data}/> and in this case data.length can is truthy when its value is not 0.

Combining && and || operators is also a great way to add logic to arrow functions without requiring you to create a block: const render = () => data.length && loading && <Component/> || 'Loading'. In this example, you basically create a ternary condition in which you evaluate the first conditions of the && half and return the last condition if the others evaluate to true, in this case our component, OR we return a loading String or in case we don't want to show anything, null or an empty string.

Nullish Operators

Recently JavaScript got a couple of new features that tap into its weakly-typed nature and make use of under the hood type coercion to work.

The nullish coalescing operator (??) is a logical operator that returns its right-hand side operand when its left-hand side operand is null or undefined, and otherwise returns its left-hand side operand.

This means that we can also use it to add logic to our variable declarations, but works differently than the AND & OR operators. Here's an example:

Using the nullish coalescing operator to declare

Using the nullish coalescing operator to declare obj's properties, will result in the following object

While we're here, we could've also used the optional chaining operator (?.) to access obj.woo.length. You may very well be familiar with the "Cannot read 'length' of undefined" error, and if you remember to use this, those days are gone. What is it and how do you use it ? Just add a ? when accessing object properties that may be null or undefined. In the above example, we would've written something like obj.tar = obj?.woo?.length ?? ["WOOTAR"] . If obj.woo was nullish the output would also be different, as the condition would evaluate to null and obj.tar=["WOOTAR"].

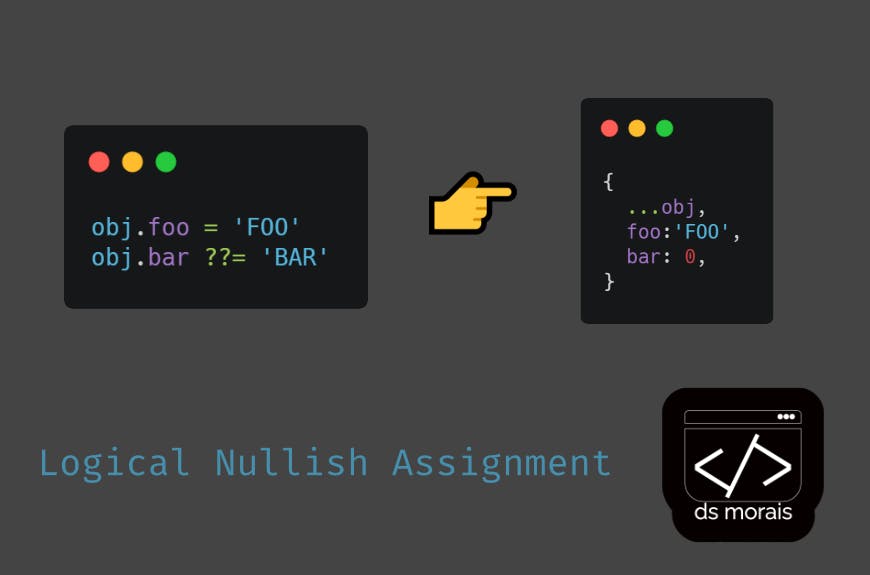

At last, there's the logical nullish assignment (??=) which only assigns a value if the left-hand operator is nullish. As an example, let's add more properties to our obj using the logical nullish assignment:

Using the logical nullish assignment to assign the

Using the logical nullish assignment to assign the obj.bar property results in the following output

These are all JavaScript features which use the underlying type coercion mechanism. And while Logical Operators may be something you use on a daily basis, understanding how the language treats different type operations can really help developers do their jobs.

Hoisting

Hoisting is another one of JS's under the hood mechanics which affects your daily work. If you use ES Lint, and as a junior you seriously should consider using it, you've probably come across the no-use-before-define rule. This discourages you from using variables before declaring them, and before ES6 introduced let and const, this rule was in place for readability purposes. This is because you can, in fact, use variables before declaring them, as long as they're declared within scope. I'll explain.

In most languages we have two contexts in which the code is read, in JS we have what's usually called Compile Time and Execution Time. Code is compiled before it is executed, and during JavaScript's compile time, it hoists all functions and variables and while functions retain their declaration value, for variables the hoisting process gives them a value of undefined.

Example:

Here's what our code looks like on Compile vs Execution Time

Here's what our code looks like on Compile vs Execution Time

This code will log undefined, David and "Hello Mark!" . This is because when hoisted to the top of the scope, our variable will get the value of undefined until it's explicitly set.

With ES6' introduction of the let and const keywords, hoisting is becoming obsolete, in the sense of its use cases disappearing, because only the var and function keywords are hoisted. The same applies to arrow functions.

Notice how I intentionally used the same name for both our global variable and the sayHello function parameter ? Yes, we'll be talking about...

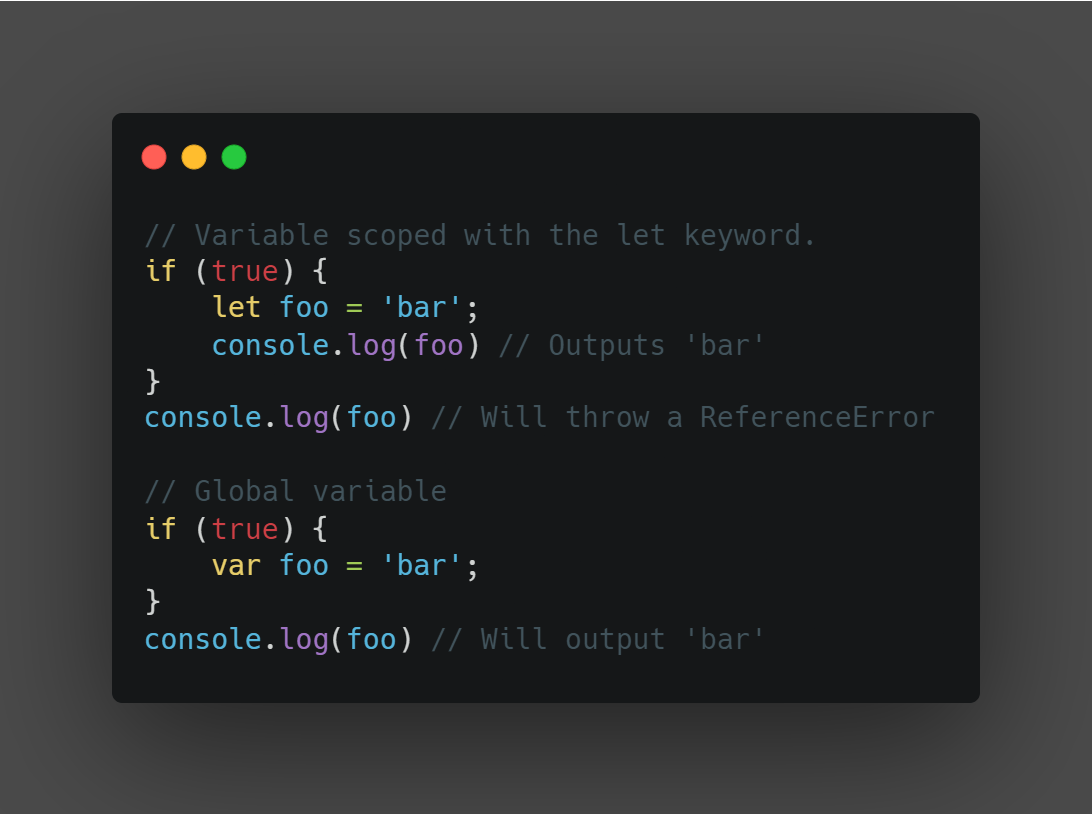

Scopes

Scope is simply the 'biome' in which our declared variables live in. In JavaScript we have the global scope and function scope. In the above example, name lives in the global scope, but when a function has a parameter with the same name, it takes precedence. This is because JavaScript will look for a variable declaration in the current scope and if it doesn't find it, it will move up to the next scope, in our case, the global scope. ES6 also introduced the block scope, by using let and const keywords, you are declaring variables that are only available within a block ({}) . Let's see an example 👇

If we use let to declare our variable, it will be only accessible within its block scope, in this case, within the if condition, and will receive an error if we try to use it.

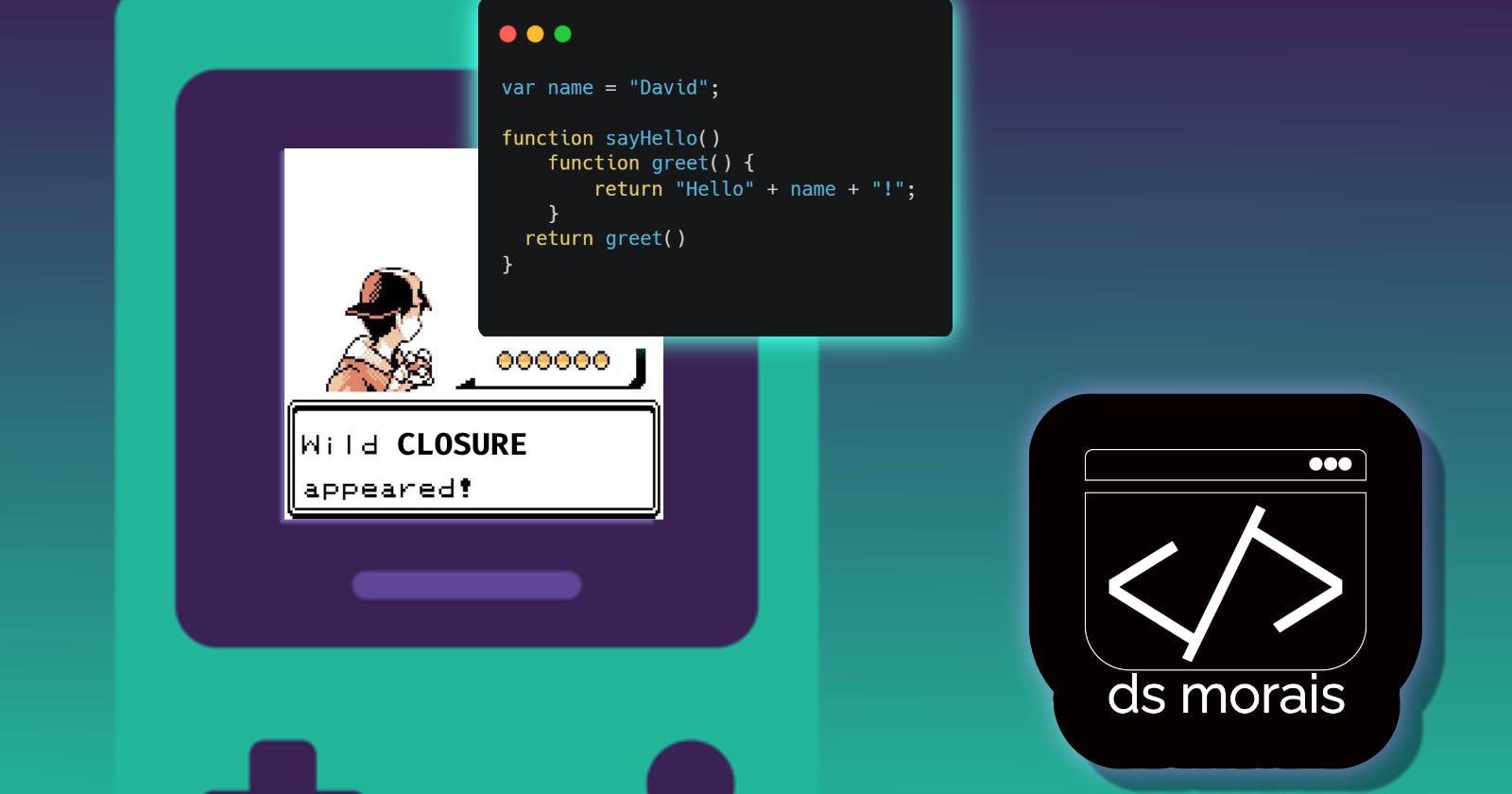

Closures

Here's something that usually comes up in interviews. What are closures ?

In my opinion, this is a rather stupid question to ask, as it's one of those JS under the hood mechanisms that developers make use of all the time, but don't even realize it exists, much less its name. I'll quote MDN here: "a closure gives you access to an outer function’s scope from an inner function.".

Let's go back to our poorly worded sayHello example, let's strip it of the console.logs, the hoisting logic, and remove the function parameter.

A wild closure appears

A wild closure appears

BAM, lo and behold, a closure. Not that complicated, and something we use on a daily, if not hourly basis, but admittedly one of the worst concepts to try and describe in words.

Now, one important aspect of closures is that the variables used within them are not copies, this means that if you change a variable within a function, its value is changed for all the scope its being used on. So if within sayHello I were to set name = 'Matt' , the variable would change for the rest of the execution, depending on where I'd call sayHello .

Conclusion

There are many more 'hidden' aspects of JavaScript which I'd like to discuss, and probably will in the future, like the Protype, Inheritance and (IIFE)(). What are your tricks and how do you use these JS's hidden gems ? Let me know in the comments.

If you liked this post, follow me on Twitter, mostly for stupid and pointless stuff, and be sure to checkout my website as I'll try to create new content at least twice per month.